Justification Of Processes

On March 10, 1988, an aircraft crashed shortly after takeoff during winter condition operations. Air Ontario Flight 1363 was a scheduled Air Ontario passenger flight which crashed near Dryden, Ontario, on 10 March 1989 shortly after takeoff from Dryden Regional Airport. The aircraft was a Fokker F28-1000 Fellowship twin jet. It crashed after only 49 seconds because it was not able to attain sufficient altitude to clear the trees beyond the end of the runway, due to ice and snow on the wings.

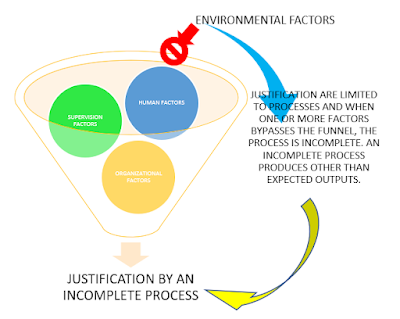

At that time there were no regulated safety management system (SMS) in place and the accident generated several safety improvements and operational changes to aviation. A question to ask is if the same accident could happen today with an implemented and operational SMS. SMS is not a system that is dependent on a specific person in charge but is reliant on processes. If processes are incomplete, then the same type of accident could happen again today with an SMS. Prior to SMS became the regulatory requirement for safety in operations, safety was absolutely dependant on individuals and their opinions. Conventional wisdom within the aviation industry is if the individual in charge of the crashed Dryden airline had not left their position, the accident would have been avoided. This is of course speculations, and speculations does not have a place for the safe operations of an aircraft or airport.

A trap for airlines and airports with an SMS is to expect that they need to be perfect and extreme proficient in their operations and have zero accidents goals and to stay safe. This leads to tampering with processes, or overcontrolling of processes by adjusting the aiming point after occurrences. When a stable process is adjusted to correct a result that is undesirable, or for a result that is extra good, the output that follows will be worse than if he had left the process alone. When a process is centered on target and is in state of statistical control, any adjustments to the process only increase variation.

Winter, snow, ice, and runway contamination seem so far away when it is in the middle of summer and hot weather. The Drayden accident happened in the month of March, which is towards the end of winter many places in the Northern Hemisphere. The pilots had flown many snowy days during their last few months of work. When they came to work that day, they expected to complete their runs on time and rest for their next duty day. There was nothing unusual about this trip until the flight crew departed with snow on their aircraft. Just a few years later Air Florida crashed into the 14th Street Bridge over the Potomac River. The aviation industry had not learned their lessons from the Dryden accident.

There is a heavy load of responsibility on the accountable executive (AE) after an accident, but when accidents are of the magnitude of Dryden or Potomac River accidents, their responsibilities just quadrupled. Recovery from accidents is not just to say or post the right words, it is to build back trust with the regulator, aviation industry and the flying public. One of the responsibilities of an AE is to ensure that the person managing the safety management system performs the duties. An SMS manager is responsible for monitoring the concerns of the civil aviation industry in respect of safety and their perceived effect on the certificate holder, being airline or airport. After a sever accidents social media ratings for an airline or airport operator involved may plummet within hours.

The fact that a captain of an aircraft is the final decisionmaker for safety in operations, there are additional responsibilities for airport operators with an approved safety management system to perform their role to ensure that their airport is suitable. Before taking off from, landing at or otherwise operating an aircraft at an aerodrome, the pilot-in-command of the aircraft must be satisfied that the aerodrome is suitable for the intended operation. Available airport information for pilots is recorded in an airport operations manual (AOM). An AOM contains information about paved and dry movement area surfaces and includes references to airside operations plans when there are deviations from AOM recordings. Where there are deviations, an airport operator is required to publish a NOTAM. A winter operations plan must include procedures for publishing a NOTAM in the event of winter conditions exists that are hazardous to aircraft operations or affect the use of movement areas and facilities. An airport has multiple options when publishing a NOTAM. They could publish that the runway is ice covered, that it is covered with slush, that snow clearing is in progress, or that the runway is closed. An airport operator may close the runway that is covered with slush, ice or snow since their obligations as an operator is to inspect the airport for hazards to aviation safety, and when slush, ice or snow are identified, there are hazards to aviation safety. A justification for maintaining such runways active may be to move aircraft to avoid congestion. It is also a role for an SMS manager to determine the adequacy of training required for airside personnel. Since an airport operator is required to inspect for hazards, they are also required to train airside personnel to learn what hazards they are looking for, and how airside personnel justify their decision that slush, ice, or snow-covered runways are hazardous to aviation safety. Decisions made by an airport operator is a required tool for an airline captain to determine if the airport is suitable for their type of aircraft operations. An airport operator who does not comply with notification about hazardous operations environment is a concern to the aviation industry and requires an SMS manager to implement corrective action plans.

Everything changed with implementation of a regulatory required SMS. Rule of thumb in the old safety world was that if it was not stated in the regulation as a requirement, the task was not required to be done. With an SMS the rule of thumb is that since a task is not stated in the regulatory text is the very same reason why an airport operator or airline must do what it takes to ensure safety. Regulations are just not broad enough to cover each acceptable work practice, procedure, process, policy, or standard. In ICAO states, flight crew are still charged with criminal intent after accidents. A non-punitive reporting policy is not necessarily accepted by the local authorities. On a clear and calm day November 1, 2022, a helicopter crashed and fatally injured all passengers shortly after takeoff. The helicopter pilot was charged criminally, and later the operator was also charged since the helicopter pilot acted on behalf of the operator. The Accident Investigation Board stated that no technical faults had been found that could explain the accident. Without technical fault the only other available justification was to lay criminal charges against pilot and operator since public perception was that someone needed be held accountable. A non-punitive safety policy is far away from a get-out-of-jail free card, but places additional responsibilities on operators and crews to do the right thing when operational tasks are excluded from the text in the regulations.

Taking off an airplane with snow or ice on the wings is one of the very first thing a new pilot learn, but for some reasons this basic knowledge is forgotten. Several years ago, a Cessna 185 pilot took off with dry snow on the tail surfaces, the tail stalled, and the aircraft pitched up violently to about a 45 degrees angle. The pilot was able to recover and continue the flight, but justification for takeoff by a several years veteran as a bush pilot was based on other priorities than safety in aviation. Air Ontario justified their takeoff and expected the flight to be normal, and the same for Air Florida and the helicopter. However, all captains had clues presented to them before starting their takeoff run, or prior to rotation, but in their ongoing mental risk analysis they all independently justified their takeoff.

An SMS manager plays a critical role in aviation safety by their roles to identify hazards and carry out risk management analyses of those hazards. These hazards include hazards other than hazard or incident reported to the SMS system but are hazards already known to the aviation industry. Since an SMS manager cannot be onboard an aircraft 100% of the times, at 100% of their locations, and analyse 100% of their risks, an operator must establish a link between the SMS manager’s risk management analyses and their operations. This organizational link is the Director of Operations or Director of Maintenance. Communication of risk analyses results with associated decision-making process are performed by flight following or dispatch, or by maintenance supervisors. For private and smaller operators, such as a helicopter pilot or a small bush plane operator, this link remains with one person, who is the captain of the aircraft.

OffRoadPilots

Comments

Post a Comment